Five Dimensions of a Wellbeing Economy

Elements That Support Thriving, Resilient Communities and Regions

Learning Guide

This Learning Guide is based on the following source(s):

- ROBUST Synthesis Report

- Transitioning towards a Sustainable Wellbeing Economy—Implications for Rural–Urban Relations

- Presentation – More Than Money: Wellbeing Approaches for Thriving Regions

- Conference Session – More Than Money: Wellbeing Approaches for Thriving Regions

- WEAll Briefing Paper: Little Summaries of Big Issues / Understanding Wellbeing

The ROBUST project evidenced, through the innovations achieved in its 11 living labs and associated Community of Practice research outputs, that it is necessary to rethink the way economic development achieves well-being, particularly with a view to strengthening rural-urban linkages.

This Learning Guide synthesizes the key messages from the analysis, which sets out five foundational elements or dimensions of a wellbeing approach to socio-economic and spatial development.

You will learn:

- why regional development models need to move beyond growth alone as an indicator of progress

- the case for wellbeing as a frame to holistic regional development

- key elements of a wellbeing economy derived from ROBUST Living Labs’ insights, with applied examples

Modules

Foundation

ModuleGovernance

ModuleIn-Practice

ModuleTools &

Resources

Economic growth is the main goal of most regional development models. But growth-based models have failed to yield thriving economies, societies, and ecosystems in most places. This is because markets demand more space and natural resources, which are limited, in order to grow.

Regions thus usually need to both intensify and expand industrial development surrounding urban areas to see economic growth. This expansion can generate short term bumps in the total amount wealth in cities, but usually leads to consequences that are ultimately counter-productive to regional development holistically, including:

Economic and social pressure on peri-urban areas, e.g., through increasing housing prices.

Pressure on the local environment, which can lead to loss of ecosystem services. When the local ecosystem can no longer provide an essential service, like erosion control or air filtration, that service will either need to be outsourced (which puts pressure on a different ecosystem) or artificially re-created (which often ends up costing more than it would have cost to conserve the ecosystem that provided the original service).

Depleting space and resources at the expense of other regions that are unable to develop as quickly. This can create and re-enforce fixed poles of economic growth that lock other regions into a trajectory of economic stagnation.

Growth-based models have failed to yield thriving economies, societies, and ecosystems in most places.

Several development models have been proposed recently that identify and present alternatives to underlying mechanisms of classical growth models that make them unsustainable. Major examples of these models include:

Distributed economy, which proposes a decentralized network of producers that prioritizes high quality products that respond to local needs, as an alternative to the present large-scale, centralized model that prioritizes mass production for a constantly expanding market.

Collaborative or sharing economy, which emphasizes more individuals, especially within communities, creating and exchanging goods and services more directly with each other, rather than principally being consumers of goods and services provided by large businesses.

Models like the foundational economy argue against using Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the basis for policy-making, and instead advocate for using indicators that more directly speak to multiple facets of quality of life. One example of this is Kate Raworth’s “Doughnut Economy” model, which grades the prosperity of economies based on a) how well people are able to live (e.g., access healthcare) given b) how damaging economic activities are to the environment.

Common to these models and others that reject an emphasis on fiscal growth is recognising the importance of promoting holistic wellbeing. Wellbeing is a concept that reflects the multiple, layered facets of economies that make life good. Models like the one reflected in the image below illustrate the interconnectedness of factors that determine personal, community, and societal wellbeing.

Diagram inspired and interpreted from the WEAll Briefing Paper: Little Summaries of Big Issues / Understanding Wellbeing.

Wellbeing is a concept that reflects the multiple, layered facets of economies that make life good.

The ROBUST project contributes further evidence that communities, especially rural ones, can be stronger and more resilient if the main goal of economies is wellbeing over growth.

Five dimensions, or elements, in particular provide a framework, based on the experiences of the ROBUST Living Labs, for a new regional development model that prioritizes wellbeing:

Services play a central and cohesive role for all aspects of wellbeing. Core services like transportation, healthcare, and education need to be accessible and reliable for everyone.

Increasing the proximity of goods and services to the people who need them is key to making communities more resilient.

Protecting and valorising ecosystems and the services they provide helps regions to balance social, environmental, and economic wellbeing.

The more circular the relationship between natural resources, products, and waste, the better economies can meet the needs of both present and future generations.

In a wellbeing economy, culture brings people together through shared heritage, arts, and traditions. Culture acts as a glue in communities, a critical conduit for knowledge that shapes values and practices.

Services, Proximity, Ecosystems, Circularity, Culture

People need services like healthcare, transportation, finance, and, increasingly, digital communications to survive. Whether people are able to get the services they need depends on both provision and access.

Service provision is a question of whether a service exists. Does an institution or a person have the knowledge and resources at their disposal to both a) have identified the need or demand for a given service, and then b) be able to carry it out to an acceptable quality standard?

Access is about whether people have the resources to get to the service they need. Resources that determine access can include physical things like personal finances or local transportation infrastructure, and social resources like knowledge about service options or a reliable support network.

A major task in a wellbeing economy is figuring out the right way to balance service provision and access to meet local needs. For example, Frankfurt, Germany, is home to one of Europe’s largest international airports, and is a major centre for the finance sector and tech industry. These industries mean there are significant employment opportunities, which mean the region around Frankfurt/Rhein-Main is anticipating continued population growth. But these industries have also contributed to the development of a significant portion of Frankfurt/Rhein-Main’s land, which has made providing affordable housing and coordinating transportation for the growing population while preserving remaining green space two of the region’s major challenges.

Why are services at the center of a wellbeing economy?

Because urban areas tend to be more densely populated than rural ones, people in cities usually either live closer to places that provide services, or live closer to inexpensive public transit options that can take them there, than people in rural areas.

Service hubs represent one model that can help connect people in rural areas with services they need. Service hubs are places that house multiple services, and all of the infrastructure needed for those services to happen, in one, central location. By concentrating where service infrastracture is necessary to set up, service hubs can save regions significant provision costs. At the same time, providing a place where people can access multiple services in one trip makes more services accessible in rural areas. Increasingly, basic services like banking and healthcare operate online. But there is a divide between urban and rural areas both in availability of reliable and fast internet, and, in turn, digital skills. In many places, expanding broadband access on a wide scale isn’t economically feasible.

Monmouthshire in Wales has piloted four digital hubs, in which village halls were outfitted with Wi-Fi, digital equipment, and high speed connection. The halls also have launched regular programming that includes digital technology training, with further training available on an hourly basis and at a low cost. The community council has also started using the halls to broadcast meetings, and can interact with viewers through Skype.

People need reliable access to goods and services to survive and thrive. Geographic distance is one facet of the proximity of goods and services, and is an especially pronounced challenge in rural areas.

But through digital and social networks, goods and services can be physically distant while being easy to access. For example, broadband allows people to use services like online banking, even if their banks are based far away.

Through globalized supply chains, most people can easily buy something made across the world at a store within a few kilometres of their home. But the level of coordination between the resource and communication flows needed to sustain networks at such a massive scale, makes them fragile, especially at their peripheries.

On the flip side, goods and services can be physically close to someone who needs them, but socially distant. For example, someone who isn’t confident using digital technology might have more limited access to timely, accurate information about businesses near them than their tech savvier neighbors.

Minimizing the geographic and social distance between people, goods, and services makes communities less reliant on distant systems or markets, and, thus, more resilient.

Minimizing geographic and social distance makes communities more resilient.

Substantial growth in the volume of traffic in and around Frankfurt is putting serious pressure on the city’s infrastructure. The Frankfurt/Main-Rhein region’s significant and continuous population growth, mainly around Frankfurt itself, has led to a sharp increase in commuters and in transport needed to meet the demands of more online shoppers. The increase in commuting time puts more distance between people and the goods and services, which are still mainly concentrated in Frankfurt, the largest of the region’s urban centers.

Making goods and services more accessible for the region’s growing population means that employment opportunities, especially for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), have to be more evenly distributed outside of Frankfurt.

This need inspired the Frankfurt/Rhein-Main’s regional authority to carry out a Cluster Study to take stock of the strengths of almost 1,000 businesses across the region. The study mapped businesses by industry, revealing “creativity clusters” that represent places across the region with a promising foundation for further business development and innovation.

Ecosystem services are the things nature does that contribute to human wellbeing. Growth-based development frameworks generally emphasize the monetary value of individual products that derive from natural resources (e.g., the market value of one liter of milk or petrol) as the basis for decision-making.

Some classic examples of market goods, like food or fiber, are also examples of ecosystem services. But an ecosystem service approach also captures the value of processes necessary for human life but that aren’t directly valued in conventional markets, like soil formation or photosynthesis.

Wellbeing economies recognize that ecosystem services rely on complex, layered interactions that drive ecological processes, and accordingly prioritize development pathways that protect nature. Essentially, this task involves minimizing the gap between a) the price markets currently assign to an individual good, and b) what the good’s actual price would be if the value of the ecosystem services essential to its provision were accounted for.

Want to learn more? The Ecosystem Services: A Natural Resource Management Approach for more Integrated Rural-Urban Governance Learning Guide provides more information about the ecosystem services approach, and gives practical examples of tools and strategies the ROBUST Living Labs used to protect nature while promoting wellbeing.

How nature supports wellbeing

With rising sea levels and increases in rainfall projected in coming decades, the region of Gloucestershire, England is preparing for a future with more frequent, severe flooding. Green space supports a complex soil, root, and vegetation-based network that makes for an unparalleled water flow and quality regulator, while providing other critical ecosystem services, like air filtration and giving wildlife a home. But with Glocestershire’s current urban development patterns, green space is increasingly being sealed. In light of these challenges, many local authorities, researchers, planners, and civil society members in Gloucestershire have noted that historically-dominant, technical interventions like flood defences are unlikely to be fit for purpose in the region’s next flood management chapter.

Methods and tools that harness or enhance nature’s capacity to regulate water flows can also be called Natural Flood Management (NFM) practices. NFM-based approaches emphasize nature’s ability to self-regulate and to bounce back from shocks like extreme weather events. Increasing biodiversity, promoting native species, and preventing the fragmentation of green areas are particularly critical to ecosystems’ resilience and capacity to provide services.

One mechanism to address rural-urban innovation in Gloucestershire’s Living Lab was to develop a competency group to plan the strategic integration of nature-based solutions in regional flood risk management. This experiment led to the establishment of a new multi-jurisdictional Regional Flood and Coastal Community sub-group to permanently accommodate the Living Lab innovations, as well as support local policies for Gloucestershire County Council’s flood risk strategy.

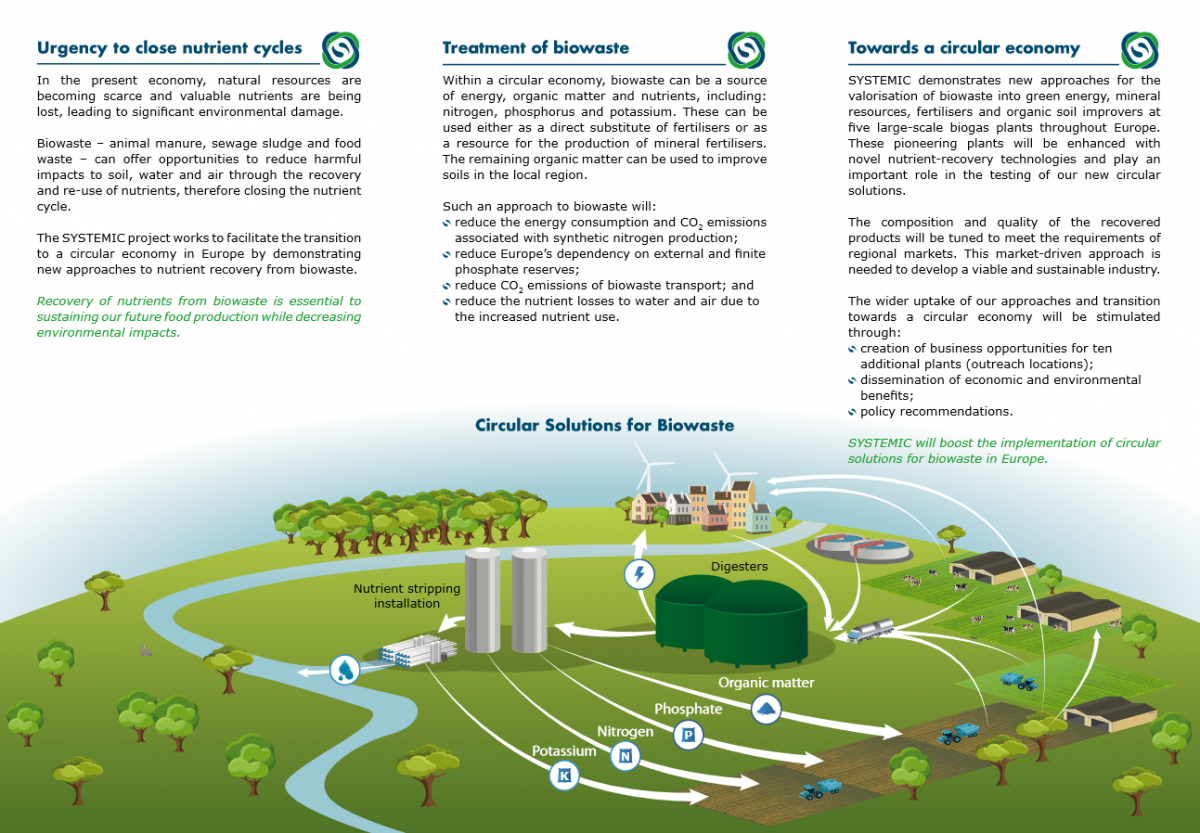

The principle of circularity — using waste as raw materials for new products as much as possible — is an important component of many economic models that prioritize wellbeing.

Raw materials can either only be used once, ever (e.g., petroleum) or are replenished through ecosystem services that are only possible within the parameters of planetary boundaries. Fish stocks can’t replenish themselves if the ocean is too acidic, for example.

Common threats to the ecosystem services that replenish stocks of raw materials, incidentally, are the extraction and the emissions from using non-renewable resources. This means that the more circular the relationship between raw materials, products, and waste, the better economies can meet the needs of both present and future generations. In practice, a more circular economy needs to rely on renewable energy, and explores new ways to convert any necessary waste into raw materials for new products or into clean energy.

New platforms and tools are also needed to help consumers get more use out of the things they have, share things with each other, and get things second-hand rather than new.

The more circular the relationship between raw materials, products, waste, and people, the better.

The globalization of food chains has come with negative social, cultural, economic, environmental and health side effects, mostly due to the scale and intensity of industrial agriculture. High tech circular farming is one model that can help localize and improve the sustainability of food systems. Methods and practices that contribute to more circular models of farming include using by-products from harvests as biomass-based fuel and repurposing food waste from urban areas to be used as animal feed or fuel.

In the Achterhoek region of the Netherlands, de Groene Mineralen Centrale (the “Green Mineral Plant) provides a practical example of ways regions can support more circular agriculture models. Individual farmers often re-purpose organic waste from their own farm to create fertilizer, but the scale of industrial agriculture often creates more waste than any individual can use. Excess organic waste needs to be professionally processed to prevent risks to the environment and to people’s health. The Green Mineral Plant processes over 100,000 tons of the surplus pig manure from Achterhoek’s farms every year, converting much of this into fertilizer.

As you learned in the previous modules, social networks are what connect people with the services that are central to their wellbeing. In a wellbeing economy, which is more decentralized and localized, communities rely less on distant markets, and need to cooperate and collaborate closely to meet each other’s needs.

Culture acts as a glue in communities, a critical conduit for knowledge that shapes values and practices. Understood as “a way of life”, culture is both the process behind and the sum of the behaviors we learn from each other over time. Communities form identities through the values, norms, traditions, rules, and other ways of doing things that they share.

Understood as “art forms”, culture is the way people express themselves and work together creatively in a given time and place. In a wellbeing economy, people come together through shared media like literature, painting, and film. A community’s culture can be reflected through “tangible heritage”, material objects or spaces that hold specific symbolic meaning, or through “intangible heritage”, like rituals or traditions.

To learn more about how culture can be used to better connect rural and urban areas, read the ROBUST Cultural Connections Learning Guide.

Culture acts as a glue in communities.

Tourism is an important part of the rural Wales economy, with visitors attracted not only to the natural environment, but also to the prospect of exploring heritage, consuming local food and traditional crafts, and attending festivals and events. However, the economic over-dependence of some communities on tourism was exposed during the 2020 spring lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When domestic tourism reopened for the shortened summer season, an unprecedented number of visitors from across the United Kingdom flocked to Wales. The record numbers created problems with traffic congestion, littering, trespassing and illegal camping, and provoked a heated debate about the social and cultural impacts of tourism on rural communities.

As a result, a new tourism approach was a high priority for the Welsh Local Government Association, and contributed to their Policy Proposal 4: Sustainable Tourism supporting local communities, businesses and people in the “Rural Vision for Wales: Thriving Communities for the Future”, whose Evidence Report was produced by the ROBUST Mid Wales Living Lab.

Proposals put forward included using smartphone apps to monitor congestion and direct visitors to less crowded sites, promoting less-visited areas to rebalance “hot spot” impacts, developing more culture-based attractions with stronger links to local cuisine and products, and regulating the number of and taxation on holiday homes.

Contributors: Sophie Callahan