Three Keys to Unlocking Rural-Urban Synergies

A Theoretical Approach from ROBUST

Learning Guide

This Learning Guide is based on the following source(s):

The Horizon 2020 ROBUST project brought together policymakers, researchers, businesses, service providers, citizens, and other stakeholders from eleven regions across Europe to better understand how to improve rural-urban synergies. The project developed a theoretical approach to identify, evaluate and envision rural-urban synergies in policy and practice. This conceptual framework highlighted three key principles for unlocking rural-urban synergies to guide the real-life work being done in the Living Labs.

This Learning Guide introduces you to the principles and how they can be and are applied in regions throughout Europe for better rural-urban linkages.

You will learn:

- What Rural-Urban Synergies are and why we need them

- The ROBUST “Recipe for Regions”

- ROBUST’s three principles for rural-urban synergies

- New Localities: Connecting the local

- Network Governance: Deciding together

- Smart Development: Growing smart

Modules

Foundation

ModuleGovernance

ModuleIn-Practice

ModuleTools &

Resources

Cities are often seen as economic engines, forging ahead through agglomeration, industry, creative capital, and innovation. Meanwhile, the countryside gets viewed as a place for food production, resource extraction and recreation – at best pulled along by city growth; at worst, left behind. Previous regional development strategies have seemed to reinforce this perception.

The rural and the urban are not separate, but interdependent. There are many complex connections between rural and urban places, people, and economies. By treating them separately in policy and planning, rural areas can be caught in a catch-up game they can never hope to win, while the reasons why cities need the countryside go overlooked. We’re missing significant opportunities to make our regions stronger, more resilient, and better places to live and work.

We now know that creating strong, mutually supportive linkages between rural and urban areas is the key to realising smart, circular and inclusive development for a sustainable Europe. We call this rural-urban synergies.

Connecting rural and urban places, people and products for mutual growth and benefit, towards a shared, sustainable future

The ROBUST project developed a theoretical framework to identify, evaluate and envision rural-urban synergies in policy and practice. This framework integrated leading scientific literature, proven good practices, and innovative policies to provide straightforward principles and practical tools to help make rural-urban synergies a reality in the ROBUST Living Labs.

The three principles for rural-urban synergies are New Localities, Network Governance, and Smart Development.

The local matters – but rural and urban places and communities cannot work alone. Even the biggest city still needs water from the hills upstream. The closest of close-knit villages still rely on distant supply chains. We need to enable connection. This means designing for shared access to systems and services, planning functional infrastructures, and activating networks between people, places and products.

Connecting the local starts with the real areas in which people live, work, and collaborate. These are called ‘localities’. Localities aren’t neat dots on a map, and they don’t always fit within municipal boundaries. We need to actively respond to how the local gets lived, not to borders that only work on paper. Our local economies cross borders, too. Doing business is about more than shops and streets – it also takes knowledge and exchange networks. The ROBUST project used the idea of ‘new localities’, a concept developed by researchers, to explore ways to better connect the local.

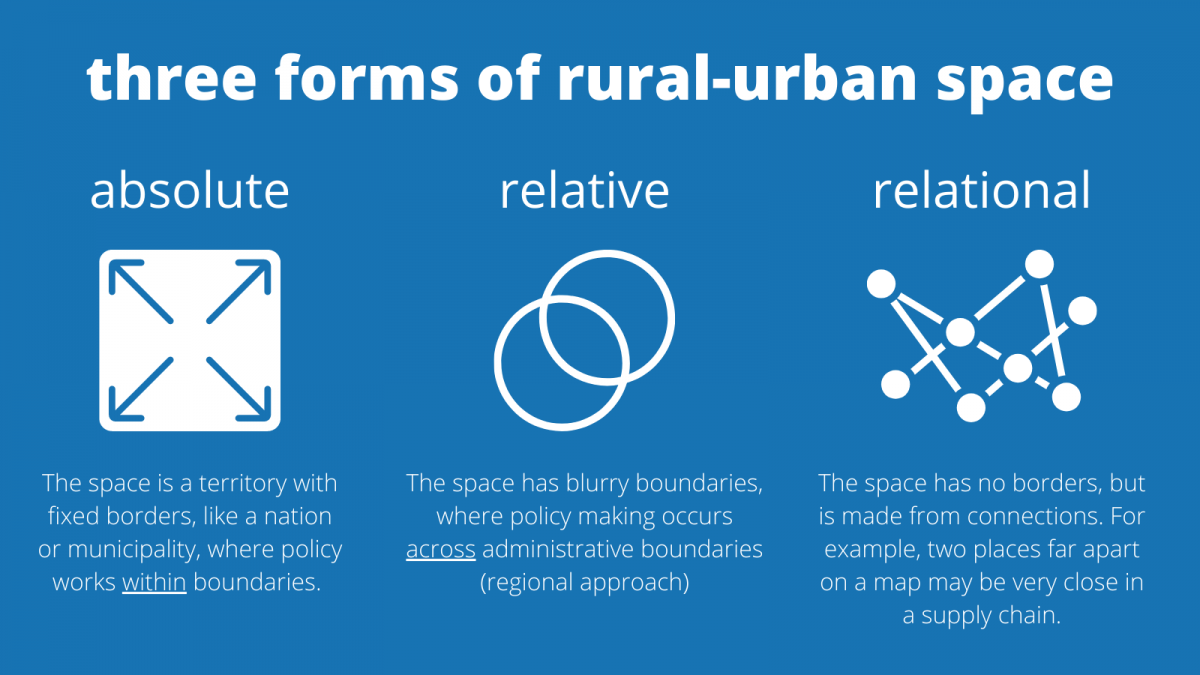

Three Different Forms of Space: Absolute, Relative and Relational

Geographers have long been interested in ‘space’ – in how particular areas of our world take form and have function. Researchers have explored how space works in society, the economy, and for government.

They identify three main forms of space: absolute, relative and relational.

When we look at how people actually live and work, it’s clear that all three forms of space co-exist. For example, a person can live in a municipality (absolute), commute (relative), and buy imported food (relational). New localities allows for this reality by investigating how and where each form of space is present in an area. This means that new localities can integrate the need for administrative or governance boundaries with how these are crossed in practice.

We need to actively respond to how the local gets lived, not to borders that only work on paper.

Some localities are just the same as official maps of towns or regions, but many are not. To identify localities, look for cores rather than boundaries. A core will be an institution or identity that a locality has formed around. Multi-Stakeholder Locality Mapping or Perceptions Mapping methodologies can help with this process.

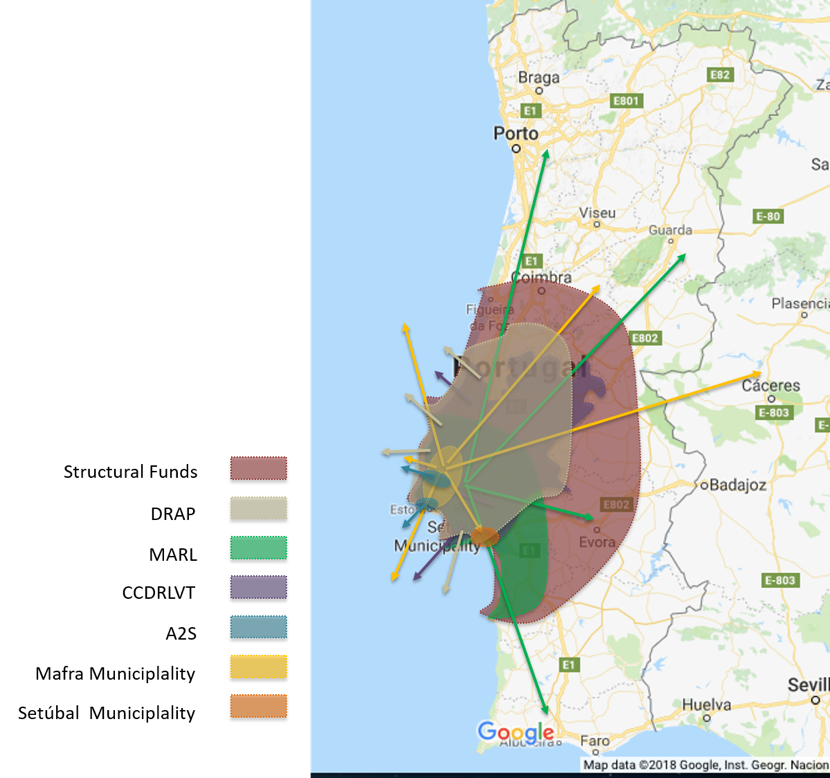

The Lisbon Living Lab stakeholders mapped their New Localities for the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. It included absolute (administrative boundaries) and relative spaces (working relationships and networks), as well as relational spaces (local and global markets).

Localities form (‘cohere’) in two ways:

Material coherence refers to the institutions and physical structures that hold a locality together. For example, local authorities, commuting zones, school catchments.

Imagined coherence refers to the sense of identity residents have for a locality and share with one another, like supporting a local sports team or attending local events.

Strong localities have both!

The Cambrian Mountains are a large area with a small population in Mid Wales, United Kingdom. Farming is a local way of life. But, the mountains don’t fall within any single local authority’s boundaries. The Cambrian Mountains Initiative is an organization that promotes development in the part of Wales that includes the uplands of Pumlumon, Elenydd, Mallaen and Llanllwni/Brechfaconnects.

With support from local communities in the Cambrian Mountains, the initiative works on increasing the profile and understanding of the region with local residents and visitors, anchoring the words “Cambrian Mountains” on marketing materials and platforms, and working to have the area officially recogised.

The Initiative’s Discover Local Produce campaign has successfully connected local producers and their products (ranging from food, drink, and craft) with urban markets, including a supply deal with a major UK supermarket chain.

Good rural-urban governance enables participation.

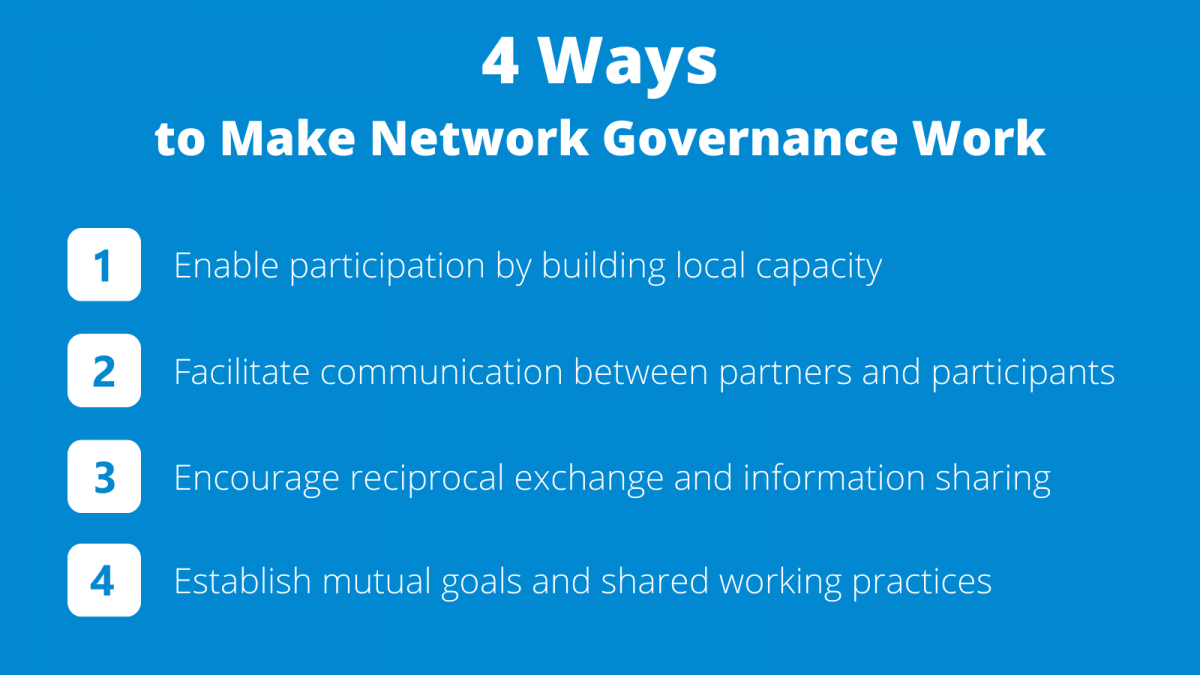

Network governance emphasises local stakeholder participation and partnerships across sectors and scales, which can help build rural-urban synergies. Real world solutions won’t be found by making top-down decisions in isolation. We need to make decisions together, involving local people and places that need to be informed from the bottom up. Network governance can create new opportunities for democratic participation and local empowerment, which can be especially welcome in rural areas. Partnerships also bring together different types of expertise and knowledge, and enhance rural-urban relations by facilitating cooperation and exchange.

One way to sum up network governance is that it gives local and regional partnerships and institutions the ‘power to’ rather than the state keeping ‘power over’. Although central government is still important, its role in network governance is more to coordinate and enable than to direct.

Together, we can design for shared systems and services that respond to everyone’s needs.

Five Features of Network Governance

- Groups from different sectors and scales are brought together in an ongoing partnership.

- They negotiate with each other.

- The partnership is formalised somehow, such as through a committee or with monthly meetings.

- The partnership has the autonomy to make decisions (although there will be external limits to what it can do, such as national laws and allocated budgets).

- There is a public purpose to the group’s work.

We need to make decisions together, involving local people and places that need to be informed from the bottom up.

Despite the benefits of network governance, there are practical challenges. Some challenges are obvious, like trust between partners and working well together. Others may be less apparent. For example, social inequalities can mean that only some groups are able to participate. Some ingredients for success can be identified.

Italian law enables ‘Food Communities’. These are partnerships between farmers and food processors, consumers, universities and public bodies. Garfagnana’s Food Community works together to decide on practical ways to support local food systems and sustain biodiversity. Local municipalities helped set the Food Community up and provided advisors – it’s the network of members who now make things happen.

The Community for Food and Agro-biodiversity was established in December 2017 in Garfagnana (Province of Lucca) as a multi-actor, cross-sectoral network governance arrangement to coordinate existing public and private initiatives, as well as promote new projects to conserve and valorise local agro-biodiversity.

The Community for Food helps maintain and share historical and cultural values for local agricultural biodiversity, knowledge, and traditions. It also represents an opportunity to set up new farm enterprises that have more resilient, multifunctional farming models. Reconnecting with local consumption is also crucial for this production model to go beyond its “niche” dimension.

Smart development is a strategy for regional growth. It involves prioritising what a specific local or regional economy can do best. ‘Smart’ here does not mean technology (although technology can certainly enable smart development), but simply taking a more intelligent approach to growth. Smart growth, smart development and smart specialisation are all ways of describing a similar idea: that regions should focus their growth policies and resources on taking advantage of their competitive strengths.

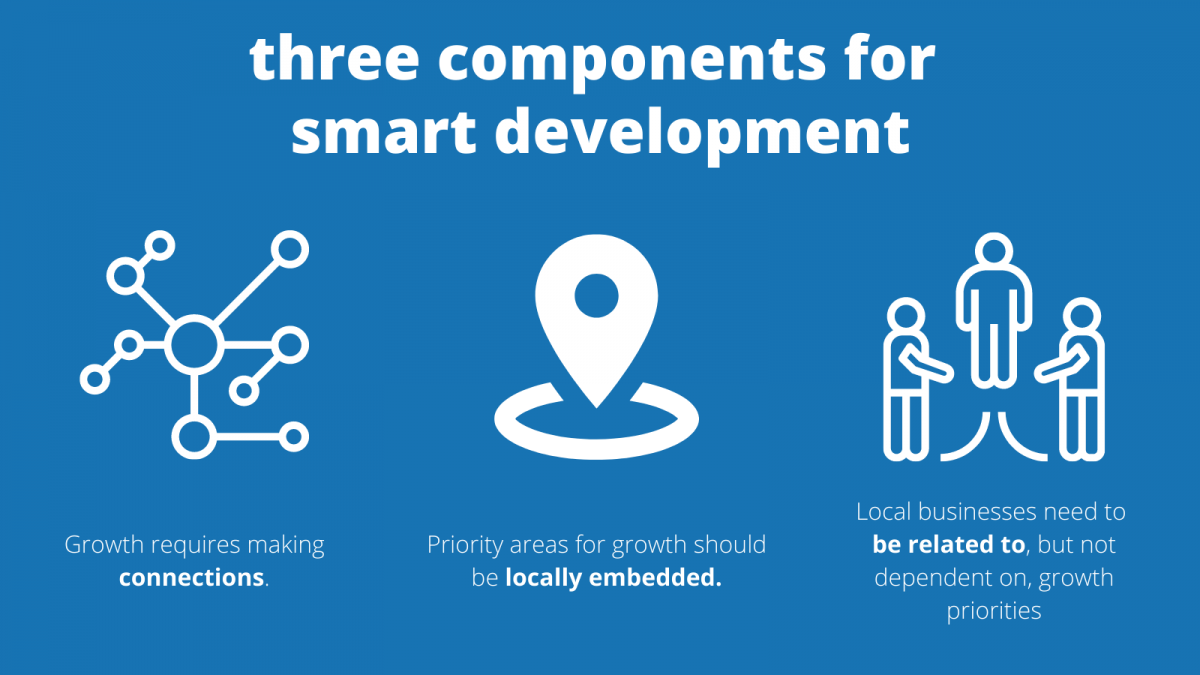

Smart Development has three key components:

We need healthy and sustainable rural-urban economies. Local economies aren’t nurtured by urban agglomeration – but nor will we meet the future by trying to preserve the past. Growing smart means prioritising what a specific local economy can do best – not what it should do or “always did in the past”. It is increasingly acknowledged that the best growth policies are not one-size-fits-all.

Instead, evidence suggests that regions are better able to grow when their strategies for growth are tailored to their own strengths and potentials. This is integral to the Europe 2020 strategy’s call for ‘smart growth’.

Rural-urban relations offer some particular possibilities for smart development. For example, rural places can develop local food or tourism industries that target urban markets. At the same time, smart development can be challenging for rural localities, for reasons ranging from limited access to amenities to mismatches between businesses’ employment needs and local residents’ skills.

Growing smart means prioritising what a specific local economy can do best – not what it did in the past or should do.

Identifying priorities is a bottom-up process, involving local businesses and regional stakeholders.

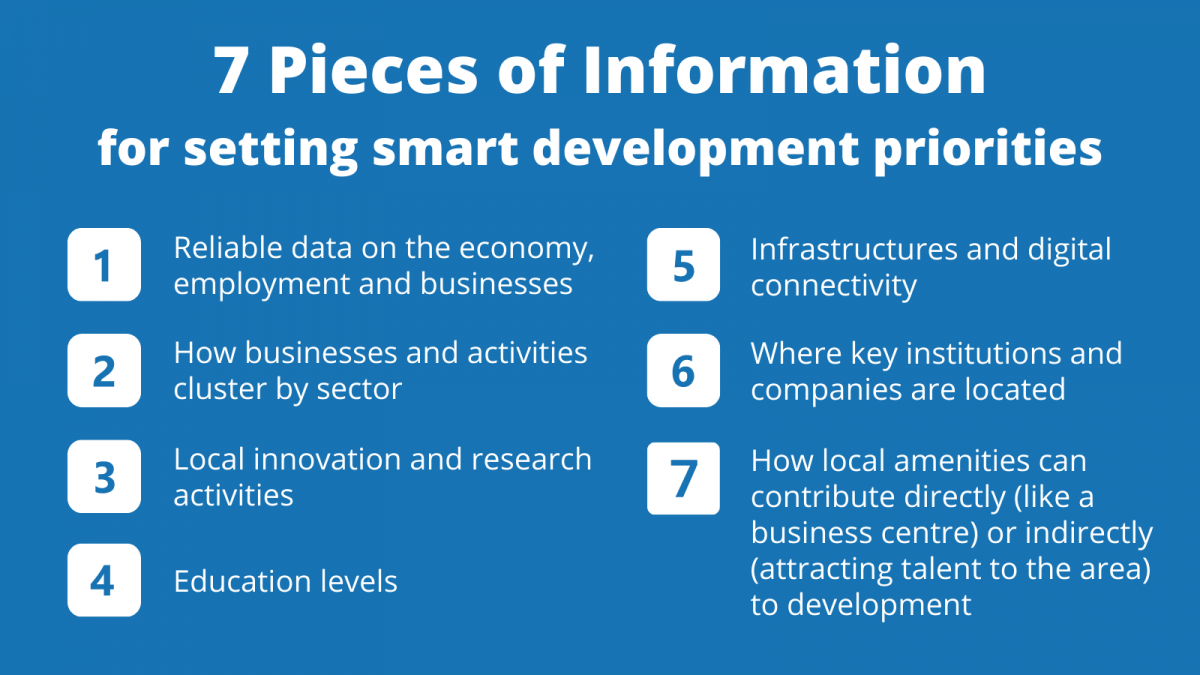

The first step is to clarify the ultimate aims of development, such as increasing economic indicators like GVA or reducing the local unemployment rate. This is important because there can be differences between what seems ‘smart’ for different stakeholder groups. Research should help inform decisions about what to prioritise.

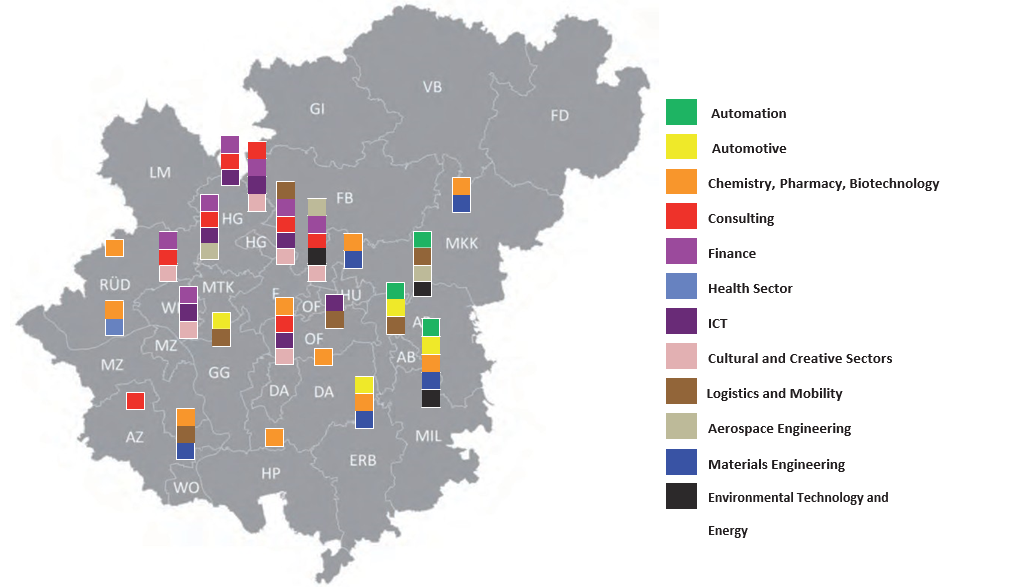

How do regions know what they do best? The 2013 report “Cluster Study FrankfurtRheinMain” (Summary and Full Report in German) surveyed almost 1,000 businesses and ran workshops with local entrepreneurs. The study contributes to a common understanding of the region’s economic strengths, thereby supporting decision-making and the identification of joint goals and strategies for regional economic development. The focus was on more effective business models, potential for economic growth and employment creation through clustering.

Twelve key regional industries – or ‘clusters’ – emerged. By prioritising business development and innovation in these clusters, the region is able to better target resources – savvy knowledge for growing smarter. However, the study also highlighted that a strategic dialogue between different actors in the region and across sectors is needed to agree on common economic development objectives.

Contributors: Katherine Peinhardt