Valencia

Live Cases

Live Cases are a real-time journaling process for the Living Lab case studies. Follow along quarterly to learn more about the experiences and lessons learned taking place in the ROBUST Living Labs.

Live Case 6: New Governance Arrangements for “Old” Challenges

Living Labs represent a new and innovative governance structure that transcends the traditional administrative boundaries of our region and has the potential to revolutionize its operation and administration. One of the various different definitions of politics is that of the science of organising human societies. If that is true, it is imperative for the prosperous, balanced and comprehensive development of any community to pay attention to the unique nature of each of the geographical areas that it encompasses. It is also necessary to tap into the intersectoral relationships that develop at the community level. This is one of the main premises and lessons that as a Federation of Municipalities we have learned during our years of experience, confirmed thanks to the experience provided by the ROBUST project. The implementation of the Living Lab has meant the materialization of an old concept that we have been talking about for a long time, but not executing: to be “glocal.”

Speaking in ROBUST terms, given the dynamics and rural-urban relations in recent years in the Valencian community, we have seen the need for collaboration between all the actors that have any involvement in the socioeconomic situation in our region. Incorporating the interests of various stakeholders and elements, that by their nature might seem likely to distort the objective of an action, is one of the examples or advice that we could transfer after our experience in this project. A clarifying example: In our case, one of the main challenges as a practical entity is to remedy the gradual loss of access to services in rural areas. This trend triggers a territorial imbalance that is increasingly difficult to overcome. The activation and deployment of local resources is one of the many antidotes to combat this tendency – and it is no coincidence that these resources are the same ones reflected in the ROBUST Communities of Practice. Returning to the example, in many commissions or meetings where we deal with challenges like uneven provision of services, participating stakeholders represent rural areas. It is often the case that these stakeholders see actors from the urban world as ‘rival voices,’ despite the fact that in working together, we have seen that they can provide solutions and not threats. This example could be extrapolated to any area or sector, and represents a common perceived barrier to collaboration.

The new approach provided by the structure of a Living Lab has led to a consolidation of networks of contacts, previously established in different administrative departments. Thanks to this new paradigm, the connecting links between actors have been strengthened, and enabled us to work across sectors.

Personal contacts between the representatives of different organizations (whether public or private) have been generated thanks to participation in new spaces for meeting and cooperation, Living Labs included. This allows for the construction of new visions and attitudes around the role of other stakeholders. These are processes of dialogue where the territory (as a social construction) is redefined, as well as the social relations (networks, behaviours, forms of coordination) between the actors that comprise it. Perhaps we are up for our next challenge: the institutionalization of the Living Lab concept as a new European governance structure.

One of the necessary aspects for a Living Lab to work is, undoubtedly, leadership. In this case, as a practical entity within the ROBUST Valencia team, this leadership is shared with our academic partner, The Valencian University. The experience gained over the years at ROBUST does not exempt this partnership from shared leadership as a path to success.

A second aspect that is needed for the good work of the Living Lab is transparency. Sharing the initiatives, ideas or projects that arise among the stakeholders will always be an enriching step toward the final objective. This sharing reinforces the breaking down of traditional boundaries between sectors and departments as they exist under current administrative structures.

Finally, perhaps one last ingredient for success is a change of mentality when facing the way of “doing politics.” As a practical partner or policy maker, we have been involved in decision making or consultation processes where challenges have been viewed as problems. This traditional way of facing the future should be overcome, and replaced with a method of enlightened politics, which is none other than the substitution of “conflict” for “problem;” a basic principle that avoids confrontation and encourages cooperation.

Live Case 5: Co-Creation during COVID-19

It’s impossible to ignore the changes that the COVID pandemic has had on our personal and professional lives; a temporary event unheard of to date, unknown to any current generation.

We allude to this fact because, as a Living Lab, one of our innovations is focused on promoting networking between stakeholders at the rural – urban and private (business, employees, etc.) – public (regional and local governments) – social (consumers) levels. Despite the challenging circumstances, the stakeholders have always conveyed the understanding and desire to continue participating in the project.

Valencia Living Lab also refers to co-creation to achieve cooperation and governance innovations involving different stakeholders related to business models and labour markets, sustainable food systems, and public infrastructure and social services. In September 2020, we were able to virutally host a workshop that was cancelled earlier in the year by COVID. Despite its limitations, the stakeholders were able to express their motivations and exchange their impressions amongst themselves.

Ten participants representing three different stakeholder groups attended the workshop: trade unions of agriculture and consumers, two mayors of rural municipalities, a technician from regional government in food health, regional rural development actors (LEADER), and even a farmer and manager of a cooperative.

The workshop’s aim was to find the best governance arrangement scenario(s), so we asked them: What should be the optimal situation or scenario in 10-15 years (considering adequate and effective management or governance)?

The most important points were related to different scenarios:

- The sustainability of rural territories, due to a complexity in administrative management at different levels;

- Towards a scenario in which public school canteens are recognized as an instrument / commitment to govern rural-urban relations;

- Towards a Food Council beyond the municipal scope from the territorial point of view.

- Towards profitable and sustainable farms that are fully connected and share value among them. A scenario in which the producer has conquered the food chain, has entered the trade and above all has come to understand how to connect with the final consumer.

- Towards a territorial structure of digital network: In 15 years a territorial structure of digital network is envisioned in which economic, tourist, agricultural development will reach all inland rural areas.

- At the territorial governance level, the supra-municipalities structures must be the main delegations in the territories with the local reality that it requires, synergies must be created with urban areas in this regard.

The main key outputs from our Living Lab work will be related to:

- Experiences of putting in productive (labour and social integration), recreational and cultural value of the nearby rural areas in relation to the city of Valencia;

- Exploring the Territorial Employment Pacts and rural-urban relations;

- Recommendations to foster imvolvement of private actors and their cooperation networks.

Live Case 4: Focusing Efforts on Resilience and Digital Infrastructure

COVID-19 burst into our lives suddenly and without warning, paralyzing many professional, social and personal activities for millions of people around the world, and significantly altering the ways we carry out our routines.

In our case in the Valencian community, it was also quite sudden. On 13 March, it was announced at mid-morning that the President of Spain was going to make a public appearance that afternoon. At that time, everyone was sure that the President was going to declare a state of alarm included in our fundamental law (similar of a state of emergency in other countries) that restricted free movement of people and vehicles, rationed goods and services, and occupied factories and industries to supply essential products.

Although everything was very sudden, it was to be expected. A few day earlier, the Valencian Community president had announced that the Fallas festival was cancelled. The festival, an expression of the tradition, culture, art and hospitality of our land (declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO), had only been postponed once before – during the Spanish Civil War. This was a bad omen for what was going to happen a few days later.

For a time, the state of alarm not only limited our free movements, but it mandated that we remain at home without leaving the building at all. In mid-March, we returned to our homes to lock ourselves up, lived together with our relatives all the time, and started a difficult phase of reconciling professional and personal life in the same space.

We had to shift quickly from working in a face-to-face environment with colleagues and access to resources that enabled us to carry out work, to another, more challenging scenario, in which work activity is carried out remotely and required resources (computers, printers, internet access) for everyone at home, including children.

Despite these challenges, we can say that we have been able to carry out the collaborative work in Living Lab in the Valencian Community. It has been very difficult, but we have been able to do it by establishing a minimum pattern of cooperation and using personal means for activities in our territory. However, we have not been able to arrange regional workshops because not all the stakeholders had means and possibility to participate. The workshop was planned for 24 March and it will be postponed to July.

Being confined at home has prevented face-to-face meetings. However, the ROBUST Valencian University-FVMP project partners have continued to work and stay in contact using the same means (phones or email), and replaced face-to-face meetings with teleconferences.

There have been many limitations. Not just with the resources to carry out activities (the resources that may or may not have had available to us, and the resources that we had to share within the family), but also the challenges of balancing and managing professional, family and personal responsibilities while in a strict lockdown.

However, we can see potential advantages with telecommuting, because you can plan all the activities in a flexible way and find the possibilities for reconciling work and personal life – perhaps in less stressful times.

COVID-19 has many dangers and issues, but it has also presented some opportunities for the Living Lab. Increasingly, organizations and people are investing in resources and establishing routines for their communication and remote working that allow us to carry out our research, thinking, and conversations, and give us access to audiences in spite of the pandemic. Optimizing work and avoiding sometimes unnecessary trips also have positive environmental effects.

It also helps us advance our knowledge about the potential of rural spaces as opportunities, and to what extent this can, in turn, contribute to a better urban-rural territorial articulation. Moving forward, we will be examining two main research themes: rural resilience and digital infrastructure investment in rural areas.

1 – Rural resilience against COVID-19: the mobilization and the response to the needs of the rural population.

There are multiple examples of how the rural population has continued to have the necessary supplies of all kinds, demonstrating that reduced mobility may not be as fundamental an obstacle as it is purported to be. The business model has positively responded to a critical situation, not only in terms of improving benefits but, probably more importantly, for community services (and hence the true social service that many of the businesses in our towns are providing), values that are so deeply rooted and that constitute such an important social asset in rural communities.

2 – Access to new communication technologies in rural areas: brake or stimulus as post-COVID-19 opportunities?

The public health crisis has highlighted that rural areas are also opportunities, and that all possible efforts must be made by public administrations to reduce the digital divide, in line with the objectives of the European Digital Agenda (which foresees that all inhabitants have access to connections of at least 30 Mbps before the end of 2020).

For this reason, we are conducting research that reaches all the rural municipalities of the Valencian Community (NUTS3). It is intended to go beyond the data provided by private companies, to examine the real situations in our rural communities.

We will be examining the availability of internet services and the degree of satisfaction, the economic sectors that are most negatively affected, the degree of digital transformation in municipalities, and the actions necessary to improve services and contribute to a significant reduction in the digital divide, thereby improving the positioning of rural areas as opportunities in the post-Covid-19 era.

Live Case 3: Making Cross-Sectorial Connections in Valencia

The Valencia Living Lab regional workshop took place on 25 September 2019 at the University of Valencia’s Research Institute of Local Development.

The workshop discussed the cross-sectoral relations between different local stakeholders across new business models and labour markets, public infrastructure and social services, and sustainable food systems. It also attempted to identify existing and potential relationships in different sectors of rural and urban areas. A total of 22 participants attended the workshop representing three different stakeholder groups:

- Public Government (13): regional rural development actors (LEADER), food security and organic agriculture. In addition to the Territorial Pacts for employment and Local Action Groups (LAGs), LEADER located in different regions;

- Private sector (2) related to the tourism and wine sector;

- Interest Group representatives (7) related to urban-consumer associations, agricultural organisations and cooperatives, as well as trade unions.

Regional Workshop with the key stakeholders held at the Research Institute of Local Development in Valencia. Photograph: Sergio Mensua (FVMP)

The key questions for the workshop were: What kind of interactions/relationships do we talk about? What other cross-sectoral relationships can be added?

Based on the previous discussions within the Valencia Living Lab, we presented the particularly relevant work areas for the cross-sectoral interactions in the Valencia region. For instance, could the LAGs and Territorial Pacts closely cooperate to support employment in remote rural areas with lower management or financing capacity?

The workshop participants were divided into six small groups to discuss the questions and draw conclusions. It was important to mix stakeholders to create diverse working groups, to best extract the possible cross-sectoral relations both across thematic domains and to regulations or information exchange.

Each group received a background document that included different examples of cross-sectoral interactions and then were asked to work together to collect their ideas on a large sheet of paper. Afterward, the groups presented their findings back to the entire workshop.

Some of the most notable findings include:

Some cross-sectoral relations already exist in some sectors, such as health and food, but there are none (at least explicitly or formally) with the governance instruments, such as Territorial Pacts for employment. Through this session, some interactions arose between the workshop’s participants. For example, the agricultural organisation of smallholders and the inter-municipal association coordinator.

Some of the strategies or actions to improve cross-sectoral interactions and rural-urban synergies include:

- Promote cooperation between territorial governance structures (LAGs and Territorial Pacts for employment) through dissemination campaigns and by strengthening the role of LAGs and Territorial Pacts to revitalise the territory;

- Extend alternative public infrastructure models to the most remote rural areas, such as demand-response transport services (e.g., rural taxi). Look at social transport incentives as financial and fiscal mechanisms;

- Decentralise public and private services (research centres, for example) to boost rural areas.

In general, the participants showed interest in attending the workshop and disseminated it through their social media channels. Most of the actors who participated in the previous focus groups for the project also attended the regional workshop, and noted that they are generally willing to continue participating in the ROBUST project.

Live Case 2: Mapping Cooperation Networks

The Envisioning phase provided a starting point for the Living Lab process, as well as common ground for discussion. First, the Living Lab team (research and practice institutions) selected potential stakeholders who could best represent the existing rural-urban relationships and governance frameworks. Farmers, landowners, planners, policy administrators and experts’ expectations differ in many ways on the overarching theme. However, it is important to realise that visions can change during the process.

Secondly, three focus groups have been carried out for this phase of work. The sessions had a greater focus on diagnosis and mutual knowledge, but also on sharing insights with one another.

This phase included envisioning new future scenarios for our work:

- New relations and cooperation mechanisms between producers-associations and administration;

- Creating new governance structures due to the superposition of competences and functions granted to the different administrations (municipalities, county councils and autonomies);

- Generating existing cooperation methods of territorial pacts for employment.

The Envisioning phase has been carried out in two steps:

The first step was to select potential stakeholders based on the engagement for sharing and interaction among them, and the following criteria:

- Involve both public and private organizations

- Consider the aims of the organization, as well as the stakeholder’s role

- If the actor wanted to continue in the whole living lab process

In the second step, we used focus groups to tackle our challenge through the different Communities of Practice: Sustainable Food Systems; Public Infrastructure and Social Services; New Business Models and Labour Markets.

Three focus group meetings were organised by topic in order to discuss the main concerns in terms of governance and rural-urban relations. The events were held at the Valencian Federation of Municipalities and Provinces (FVMP) offices and each event was recorded (audio and video).

The same methodology was used for each focus group meeting. Experts gave a presentation on the ROBUST research aim, the Valencia case study, and Living Lab methodology. Then, regarding rural-urban and governance linkages, the focus groups provided a characterization of each stakeholder role for sharing; an analysis of the presence and/or links in the rural-urban territorial scenario; and then, which governance mechanisms each of the stakeholders participate in and how. Likewise, it also tried to envision where they could additionally participate.

The focus group participants were asked to answer one question about cooperation to give us an idea about the likelihood of future cooperation. The question was: “From this event, how likely are you to start new projects with the different actors (in the focus group)? 1 (not likely) to 5 (very likely)”. Relationships identified as 4 (likely) or 5 (very likely) on the Likert scale were used to form the potential cooperation network.

Main outputs

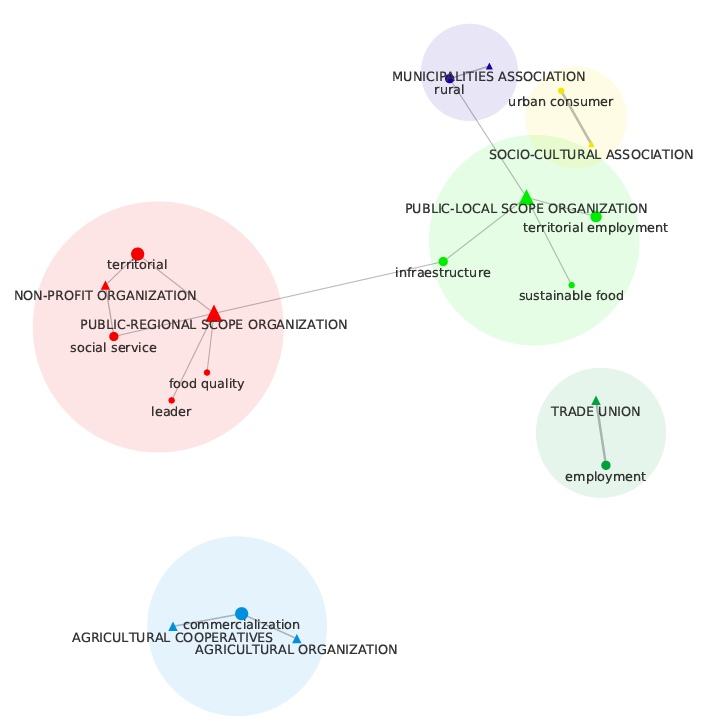

We developed an overview of the different relationship types by role. In general terms, the focus groups allowed us to capture the main views through the different stakeholder’s roles. As shown in the figure below, it is possible to compare among organizations and identify multiple roles.

Combined mapping and clustering of the role by stakeholder group

The findings from our work with the thematic focus groups revealed some important considerations to be taken into account:

Sustainable food systems:

– The stakeholders emphasized that there is a global problem: low profitability in production.

– Many actions from policy-makers, agricultural organizations and civil society stakeholders around the more sustainable and proximal production are being taken.

– The role of agricultural cooperatives was recognized and the importance of generating added value to improve profitability. However, agricultural cooperatives have structural problems at the municipal level (e.g. aging, oversizing in terms of human resources) making it difficult to become main drivers of agriculture, especially in sustainable food systems.

– Strengthening the relations and cooperation mechanisms between producers-associations and policy-makers was an important issue.

Public Infrastructures and Social Services:

– The LEADER strategy has proven to be the best example of territorial governance in rural areas, since it transfers the ability to design their own development strategies to local communities (through a bottom-up approach) and has a tradition in many areas.

– Some of the proposals were claimed to be an option to present in LEADER. The larger private initiatives that could stimulate the growth of these territories was appealed.

– Regarding social services, there is a weakness due to the superposition of competences and functions granted to the different administrations: municipalities, county councils and regional governments. Thus, thought should be given to how structure a regional model through the territories by creating supra-local governance.

New Business Models and Labour Markets:

– There is a shift towards multi-level governance through the territorial employment pacts. Eighty percent of the municipalities in the Valencian region are integrated into the territorial employment agreements. However, governance structures in inland rural areas are not operational and lack coordination among them, unlike those in the peri-urban areas.

– On the other hand, initiatives focus on a single municipality. It is hard to extend the territorial strategy from Valencia city.

– Different proposals were mentioned: create a territorial pact for the development; and study the Integrated Territorial Investment as an intervention mechanism for territorial development in rural areas.

Focus group with key stakeholders related to Public Infrastructures and Social Services, including policy makers of LEADER strategy; mobility planning and social services; municipalities association; and a private social service institution. Photograph: Sergio Mensua (FVMP)

Future Cooperation between Stakeholders

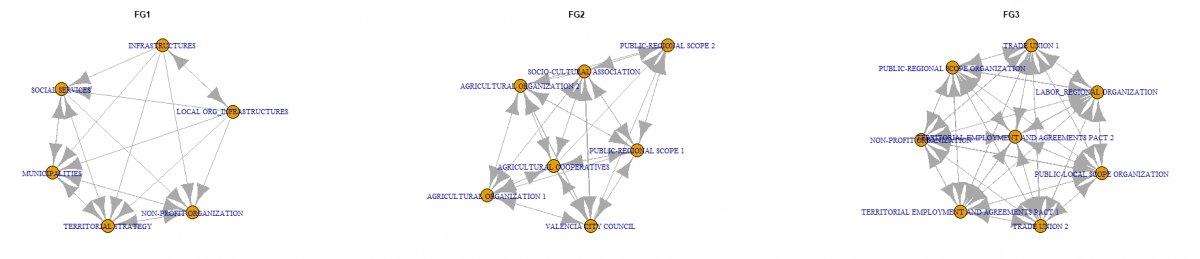

From our analysis of the focus groups, we found different potential cooperation links. In the Sustainable Food Systems (FG2) and New Business Models and Labour Markets (FG3), there is a tendency for the actors to cooperate. This trend is different for the actors working on Public Infrastructure and Social Services. (FG1).

Future cooperation between stakeholders within the three focus group. FG1: Public infrastructures and Social Services; FG2: Sustainable Food Systems; FG3: New Business Models and Labour Markets.

According to our expectations, we can refer to the social networking among stakeholders at the different levels in order to identify what rural-urban relations are being generated. We have detected an interesting participation and potential collaboration among them (e.g. the case of agricultural members or the LEADER strategy together with municipalities association, as well the private institution of social service with the policy-makers).

Likewise, recognising the importance of having territorial governance instruments and encouraging their use where they are already established is key, as illustrated by the Local Action Groups (LAGs) and the territorial employment and agreement pacts.

The latter, in particular, need more proactive engagement by local institutional stakeholders. Both governance structures could potentially have a joint role and cooperation possibilities in overlapping territories.

Live Case 1: Strengthening Networks in Valencia

It is important to highlight the established dichotomy between the political (Valencian Federation of Municipalities and Provinces) and scientific community partners (University of Valencia). Both are active institutions in the same territory, geographically located in and institutionally recognised by the city, but which have developed on parallel paths. The Valencia Living Lab offers a new horizon for both. It provide opportunities for possible meetings between teams, pooling projects, and ways to work and contribute ideas. It is also an opportunity to unite two worlds – academic and institutional – which have previously been somewhat removed from one another.

Today, the University of Valencia team has access to most of the agenda of the municipalities, participatory agents and decision-makers of the Valencian territory (stakeholders). The Federation of Municipalities are dealing with a diverse array of issues in the framework of territorial dynamics and socioeconomic development support for the municipalities, especially the smaller ones. The ROBUST project has created a win-win situation for both.

It was not until recently that the first focus groups were embraced in our Living Lab. These meetings were some of the most innovative experiences the team had. All the participants were aware that our region has a rural-urban polarity around the different Communities of Practice. As a result, there are increasingly complex territorial, social, economic and landscape realities and tensions that must be managed. Likewise, creating new governance structures or being involved in existing ones is directly and fully related to governance issues.

Opportunities

We will use social networking among stakeholders at the private (business, employees, etc.), public (regional and local governments), and social (consumers) level to identify what rural-urban relations and governance models are being generated, and to explore what effects they are having on development processes. The case studies are really interesting because of the increasing public interest in urban-rural relations around local food systems, and new business models and social services, as well as improved transport infrastructure. The strong relationships will hopefully increase participation and contribute to better assimilation of the processes of economic and social diversification by the stakeholders themselves. It will also allow policy-makers to identify obstacles to effective development measures and facilitate the implementation and change processes.

Challenges

Generally speaking, our challenge as a Living Lab is to supply public services to an unequally distributed population in a very large area. We are curious to follow other Living Labs in the project to see if bringing urban benefits to the rural world generates a positive chain reaction within the private sector. Comprehensive development strategies are needed both for the region and for individual areas in order to manage the resulting challenges and take advantage of opportunities. The task is challenging because it clashes with the political-administrative structures, who are accustomed to working independently over short periods.